House of Secrets: The Burari Deaths, a three-episode Netflix series made by Leena Yadav, takes us through the theories, ideas, truths, as fabrications surrounding the strange affliction that shocked Delhi.

The bone-chilling discovery of ten bodies hanging “like the roots of a banyan tree” in a Delhi suburb one morning in 2018 was the result of a lethal mix of undiagnosed mental illness and patriarchal customs of the normal Indian joint family.

Leena Yadav’s documentary investigates the strange murders of 11 members of the Bhatia family, who lived in Burari, New Delhi. We follow the unsettling story of three generations of a family being wiped off in a single night, seemingly without reason or rhyme.

There was no evidence of a struggle, yet it’s difficult to comprehend how eleven family members, all of whom were in different stages of life and still had a lot to do, perished by mass suicide. It was categorized as either suicide or murder. Nonetheless, it was both or neither at the same time.

How Mental Illness and Patriarchy Stigma Influenced the Burari Deaths?

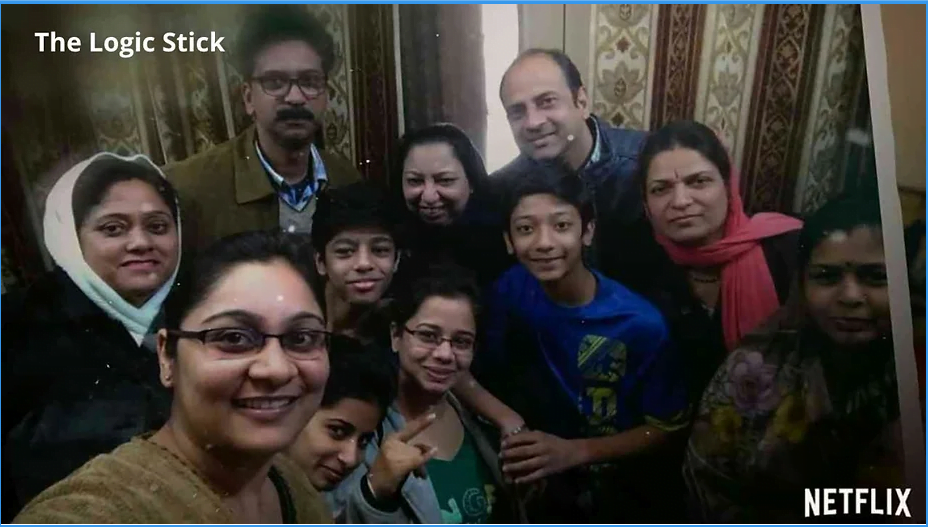

The Bhatia family appeared to be a totally “typical” Indian middle-class joint family by all accounts. Shivers go down the spine when images of the family in happier times are juxtaposed with their untimely mass demise.

The revelation of diaries outlining the “Banyan tree ritual” in an educational manner, as if a “third entity” was manipulating the entire family, is particularly startling. The most disturbing aspect of it all is the understanding that what happened to them might have happened to any other family at any time. Most families already have the components for the recipe: blind allegiance to a patriarch, denial of mental illness, shame, secrecy, and excessive control over each family member.

The documentary raises awareness about mental illness stigma, but it is evident that there is a gendered component at work. After undergoing trauma, Lalit Bhatia, a middle-aged man, supposedly had an undiagnosed mental ailment. This finally led to him hearing his dead father’s voice, according to doctors who investigated the case for the documentary.

The patriarch’s death left a hole in the family, which Lalit Bhatia ostensibly filled by acting as a conduit for his father’s voice and leadership. It is difficult to overlook how mental illness in men, when combined with superstition ad faith, distorts patriarchal family relations into a hideous doppelganger, bringing patriarchal systems of control to their logical and severe extremities.

Lalit Bhatia is said to have suffered from long-term psychosis, which turned the family into a little cult. The potency and attractiveness o the authority figure in cults, according to one researcher, lies in their defiance of moral expectations. But it appears that the missing piece of the puzzle is that a man in a position of power within the family was able to actualize his authority through his mental illness, rallying superstition to legitimize the disease.

This is what gives the documentary its relevance. It comes amid growing discussions about how superstition divides societies and how its potency lies in its tacit invocation of anxieties about changing norms.

Superstition, as in the case of the Burari family, may not have the same impact if it weren’t for underlying patriarchal worries. But, as experts point out, a young woman’s engagement was the catalyst for the ultimate deed, which came after years of domination by the apparent patriarch’s spirit. Lalit Bhatia allegedly withdrew inside and appeared out of sorts, fearful of losing control; ten days later, all eleven family members were dead.

The lens of Leena Yadav paints a nuanced portrayal of how socioeconomic fears, patriarchal traditions, ad a denial of the truth of mental illness all interact to have terrible results. Overall, the case demonstrates that mental illness affects more than just one person. If they are powerful enough, they can drag multiple others into an orbit that, if left unchecked, descends into disaster and decay.